Mara G. Haseltine Interview: STRAIGHT TALK Oct 2015 Issue (Images at end of the text)

1. How did you get involved making environmental art?

I have always been inspired by the natural world. I remember summering in Maine as a child in the 1970’s and thinking, “This world is perfect.” I was always curious about the biology of things and what made them function. As I learned more about biology, I discovered that the world was plentiful in biodiversity, existing in a functioning balanced biosphere. With the onslaught of anthropogenic induced climate change I have been a first hand witness to the decline of my “perfect” bio diverse world as we enter the sixth mass extinction. Even in its diminished state the natural world still captivates me and–remains my muse to this day hence my need to protect it and make environmental art and activism.

As I became involved with environmental activism, I began to make artwork that reflects our need to address the environmental crisis on both a functional and solutions-based level—and also on an emotional level, to create awareness, because I firmly believe our cultural evolution affects our biological evolution.

2. You are a big advocate of geotherapy, which your website describes as a solutions-based practice aimed at addressing today’s environmental ills. Can you tell us more about geotherapy and how it plays a role in your work?

“Geotherapy” was first coined in 1991 by a panel of scientists led by Richard Grantham and Van Rensselaer Potter at Conference at Université Claude Bernard in Lyons, France. In their manifesto Declaration for Geotherapy and Bioethics they predicted the massive devastation of our biosphere overpopulation could potentially cause. The manifesto was a call to action describing a global bioethic that could be put in place to encourage scientists to become aware of, and responsible for, its practices affecting the long-term habitability of the biosphere. The manifesto was also an acknowledgment that anthropogenic disruption is rapidly making the planet uninhabitable– yet it was hopeful, because these scientists believed that social and cultural evolution could occur within the scientific community, resulting in long-term solutions. And that, in turn, would have a profound effect on our cultural and biological evolution. The idea that our cultural evolution affects our biological evolution has had a profound effect on me as an artist. In all my work, I strive through form, function, materiality, and awareness toward the end of affecting our shared cultural and therefore biological evolution.

For me, it is very important that the word “geotherapy” was coined by scientists, but when I posted the manifesto on my website I made one small but significant edit: I changed the word “scientists” to “people,” so the ending now reads, “We declare that people of all walks of life should adopt the aforementioned goals and participate in meeting at all levels to apply these principals.” For it is the job not just of scientists to create solutions for these problems. Every living being on the planet is affected by climate change; therefore we must all embrace a bioethic requiring humans to become stewards of the planet and our shared biosphere.

I love the word “geotherapy” because it is rooted in action and an outlook on the world, as opposed to words like ‘organic’ or ‘sustainable,’ which have been co-opted by the advertising industry, whose meanings therefore have become mushy. One does not have to be a scientist to practice geotherapy. Any actions big or small can fall into the category of geotherapy– from picking up litter to voting for a clean water bill or deciding to purchase fair trade goods. Geotherapy is a call to action that I practice in both in my private life, as an environmental activist, and my public life as an artist.

3. In February of this year, you delivered a lecture at the School of Visual Arts regarding the important merging of geotherapy and art, stating that the union “has the power to catalyze a shift in global consciousness and cultural awareness” in order to preserve and better the environment. For those unable to attend, would you mind talking about your ideas further for our readers?

Artists often act like antennae for society, picking up advance signals of change. Artists reflect the society and times they live in, but often at a one-step remove, which can create acute awareness of both self and society. Right now, humanity is living through history’s sixth mass extinction, yet most people, though they may have heard these words, feel powerless to change this fact and do nothing to address it– as if it does not directly affect them or their offspring! It is through the lens of art—whether music, poetry, dance, or visual art–that people can connect to such vast concepts as mass extinction on an emotional level. Art allows room for the viewer to engage with environmental issues on a personal level; it has the power to show us that beautiful, functional solutions are available. Good environmental or political art is engages viewers, so they are compelled to take action. In fact, art is an affirmation that the viewer is human and can take action.

My main technique is to create work that is visually alluring and beautiful, it is through this that the viewer becomes drawn into the a narrative as with the depiction of a sub-molecular proteins in my public works, blown up to megascopic proportions. The viewer’s engagement with the beauty of he natural world makes that world that much more precious and relatable. The natural world not only gives us sustenance–water to drink, air to breathe, and food to eat– it also provides beauty, mystery, and inspiration. As an artist inspired by science, I am aware of, and awed by, the incredible array of tools we have at our disposal to see into the most minute or the farthest corner of the universe.

4. In your series La Bohème: Portrait of Our Oceans in Peril, a sculptural and operatic performance piece, you incorporate uranium glass, a material that gives off a strikingly eerie green glow when exposed to UV light. What is the significance of using uranium glass in your this series?

There are several reasons for using uranium-infused glass in these works. Many of my works derive from microscopic muses that I see fluorescing under the microscope, just as many life forms bio-fluoresce in the ocean– so I was emulating that, with the uranium glass. In addition, La Bohème: Portrait of Our Oceans in Peril is about how are oceans are literally becoming toxic on a microscopic level. I was heartbroken when I began collecting samples from bodies of water all over the planet and found micro-degraded plastic in all of them. These microscopic plastic particles are being consumed by plankton and entering the food web. I was also well aware that this was just the pollution that I could see through the microscope and that factors like ocean acidification are also distressing our waters. I asked myself how could others begin to feel the sadness I felt while witnessing ocean pollution first hand through the microscope? With the creation of La Bohème: Portrait of Our Oceans in Peril a tragic love story, I was striving to create a scenario people would be captivated with and could relate to on a very basic and human level. The sculptures have been used as set pieces in live performances and a short video based on Puccini’s opera, La Bohème, set in 1840’s Paris. La Bohème depicts the poor young poet Rodolfo, who falls in love with Mimi, a young grisette who is dying of consumption. However in this case, Mimi is a sculpture of a tintinnid plankton ensnared in micro-degrading plastic–a representation of our ailing oceans.

My use of uranium was not just because of its luminous qualities but also to address environmental concerns on a material level. Something I frequently say is “Uranium for art, not bombs.” And in fact uranium was used in non-toxic pressed glassware until the 1940s and the advent of “Little Boy,” the first atomic bomb. Toxic materials like plastic and uranium should be sequestered and preserved in fine art, in museums and galleries, or for for medical devices and jewelry. Plastic and uranium, are not inherently evil; it is the way these materials are used and improperly discarded that is the issue.

5. You have done a lot of environmental works focusing on marine life, specifically oysters. What draws you to marine life?

I have been drawn to the ocean for my entire life. I am fascinated by it, as we are water-based life forms. The ocean is so familiar yet so vast and unexplored– like outer space. As I have become intimately connected to the ocean through collaborations with scientists I have found that it is not only a food source, it actually regulates our atmosphere through sequestering carbon dioxide and provides at least half of the world’s oxygen. Without a healthy ocean, life on our planet is doomed.

My fascination with oysters began as a small child, since my family was involved in the pearl business in Japan. I was surrounded by pearls from the South Pacific of all shapes and sizes, and was mesmerized by their luster and iridescence. But my interest in oysters also came from an intense need, later in life, to find a naturally occurring way to filter water. One oyster has the ability to filter up to fifty gallons of water a day! Since New York’s waters once sported 500 square miles of naturally occurring reef, I thought, What a great way to both build habitat and shoreline protection, and to filter water.

6. Your piece Transcriptease (2007) is called New York City’s first solar-powered oyster reef, shaped like a double helix and installed in College Point, New York. [In your statement for the piece, you mention that a typical oyster midden creates a variety of problems for oysters such as clustering and starvation and that your vertical midden allows for water to flow freely to all oysters so that the maximum amount of nutrients are received.] Years later, how are the oysters faring on your pieces?

The reef at College Point is an experiment and a functional artwork, incorporating an electrolytic process that accretes calcium carbonate, the substance shells and bones are made of. I studied this technique for coral reefs in Indonesia an adapted it for oysters, this technique is commonly referred to as “biorock.” The calcium carbonate part is working really well, which is great for shore protection. Near the negatively electrified area, the anode, we are seeing larval settlements of oyster spat. A happy surprise is the spartina– a reed common to wetlands that creates shoreline protection and sucks up heavy metals in the sediment– is doing remarkably well growing twice as tall as its un-electrified counterparts! Our results need to be tested on a much larger scale and at several depths, to really see its viability.

The thing that I would like to point out is that this art-science project and experiment captured the viewer’s imagination and spurred on the entire movement to restore New York’s oysters, which is in full force today.

7. You are just starting a residency at St. Joseph’s College in

Long Island, New York. What do you have planned during your residency?

I will be exhibiting Rose, a series of photographic portraits I made of the astrangia poculata, a coral from Cape Cod, Massachusetts that is typical of the kind that inhabit mid Atlantic waters, a polyp considered by International Union for Conservation of Nature “of least concern”—that is, not particularly endangered at the moment. These corals are sprouting like dandelions at a time when tropical corals are dying at a rapid rate worldwide. The question arises could these deep water corals be the ones that survive a mass extinction?

I will also give an artist talk, which is open to the public, and a series of workshops for both the art and science students based on collecting specimens from the field, which in this case is their campus, which includes a pond and wetlands. We’ll be looking at our findings under microscopes and making a series of sculptures based on what we see. The goal is to give students a fast-paced tour of my own art-making practice and inspire them to make art using scientific methods on their own. I hope it will also teach them the value of their own observations and field research.

8. You are currently having a show at the Tatiana Pages Gallery in Harlem, New York with a new body of work. Can you tell us about this?

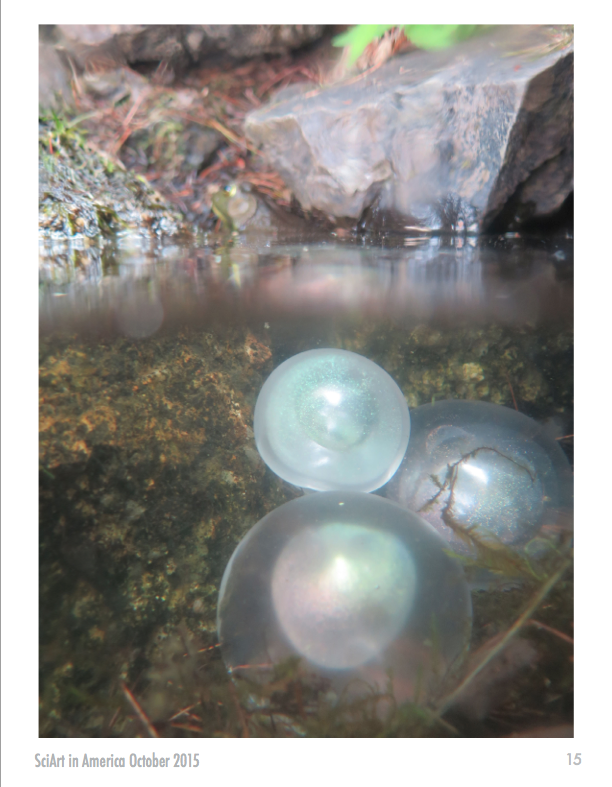

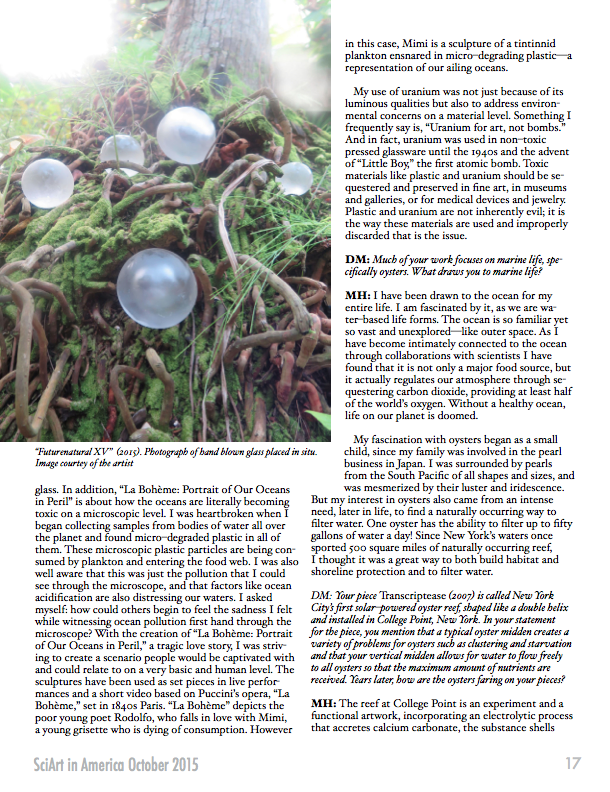

Yes– the show is entitled Supernatural-Futurenatural, and in many ways is a departure from other bodies of work of mine, in that it is not literal. Though many of my sculptures look abstract, they are in fact accurate renderings based on scientific data or observation, and are in fact morphologically correct. Supernatural-Futurenatural imagines the ability of our beautiful watery biosphere to regenerate and create new, yet-unknown combinations of future life forms. Summarizing a six-month series of performance-like rituals, Futurenatural-Supernatural presents photographic work in which objects I created were placed in natural settings– for example, forests and tide pools–and also examined in the lab on a microscopic scale. In addition to the series of hand-blown glass objects I photographed in natural settings I also created a new substance in the lab, called “GPF

Caviar,” combining molecular cuisine “pearls” with green fluorescent protein to make them glow. The show also incorporates a sculptural installation of carved wood and the glass objects depicted in the photographs, creating an “incursion” into the gallery’s space in the form of a surreal and mountainous range in which luminous pale green glass seems to grow, depicting a future life cycle. The installation is supported by two large mural scale prints of the objects in situ.